HOW SAFE IS IT?

Safety is issue number one in flight training!

How do student pilots stay safe while learning?

What happens if the engine quits?

Aren’t most aircraft accidents serious?

What about weather accidents?

What about midair collisions?

Obviously, it’s important that aircraft be reliable mechanically. What’s the record on this?

What about running out of gas?

How does one stay up-to-date on the latest safety information?

When someone considers learning to fly, the question of safety invariably comes up:

How safe is flying in a light airplane? How safe is driving a car or boat?

It depends on the circumstances, the risk tolerance of the individual and a willingness to keep learning!

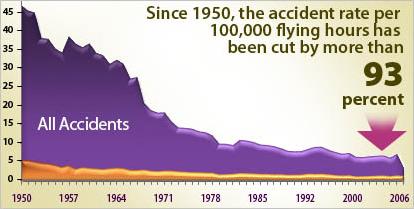

Compared to automobiles, General Aviation—defined as all kinds of flying except for the airlines and military—has about one-sixth as many accidents on a per-vehicle-mile basis, and the accident rate is stable. There are several reasons why. Training for a pilot certificate is much more rigorous than it is for a driver’s license. Mandatory ground and flight training, along with written and practical tests, help to ensure that pilots have achieved a basic level of proficiency. Periodic recurrent training helps to maintain and improve skills.

The environment in which aircraft operate is much more closely regulated, as well. The regulations have evolved over the years to address accident prevention, and most pilots prefer to use regulations as a minimum guideline to exceed in their own flight operations.

Perfect safety is unknown in transportation and probably in most of life’s endeavors. Our expectations have been based largely on the airline safety record. By almost any measure, commercial air travel is probably the safest mode of transportation. This is because of the tremendous emphasis that is placed on the reliability of aircraft, air crews, and the air traffic control system in which they operate.

General aviation uses many of the same procedures as the airlines to achieve a good safety record but the record will not match the airlines for the same reasons that pleasure boating is not as safe as traveling on an ocean liner. The aircraft are different, the pilots are different, and the objectives are different. But just as the diligent and cautious boater can operate safely while recognizing the limitations of his or her craft, so too can general aviation pilots. Pilots who develop and maintain their skills can fly with exceptional safety and derive maximum pleasure from this exciting activity.

How do student pilots stay safe while learning?

Pilots learning to fly are placed in a system that provides checks and balances to ensure that they aren’t exposed to dangerous situations before they have been given the necessary knowledge to cope.

Prior to flying alone, student pilots must complete a written examination and have demonstrated proficiency in all activities relating to local flying, including emergencies. So when you take the airplane up for the first time by yourself, you will have been drilled many times in what to do in case something doesn’t work as planned. Essentially, the same approach is followed prior to going on long solo trips, called cross-country flights, away from the airport. New pilots stay under the watchful eye of an instructor until they are ready to go out on their own.

What happens if the engine quits?

That may be the most-asked question of pilots since the age of powered flight began. First, it should be noted that aircraft engines very rarely quit. Most pilots will fly their entire lives without a major engine malfunction. The engine is designed with dual ignition systems and two spark plugs per cylinder so that, if one system fails, the engine will continue to run on the second system.

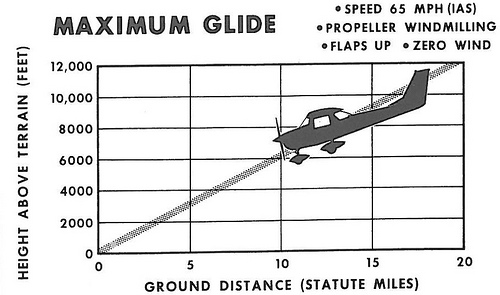

But anything mechanical can fail, and if it does the aircraft is balanced to become a glider. The nose of the aircraft will dip slightly below the horizon and assume a stable attitude. Although the engine may have stopped producing thrust, the wings are still producing lift, so a typical training aircraft can glide as far as 9 miles from an altitude of 6,000 feet above the ground. The pilot has full use of the flight controls to turn and descend. While a forced landing seldom happens, pilots are trained to look for safe landing sites, such as an open field, just in case that one-in-a-million malfunction occurs.

Aren’t most aircraft accidents serious?

In reality, about three quarters of all aircraft accidents result in little or no injury to the pilot or passengers. It depends on the type of accident. Fender benders are much more likely. The aviation equivalent to the fender bender is the landing.

Just as with automobiles, certain incidents are serious. A head-on collision in a car, is usually severe. Aviation weather-related accidents are bad and we’ll discuss them momentarily.

On average only one GA accident in five results in a fatality. That’s worse than automobiles why. Light aircraft travel three to four times as fast as cars thus more energy has to be dissipated. New aircraft designs are coming out equipped with whole-aircraft parachutes and with airbags. This will improve the statistics.

What about weather accidents?

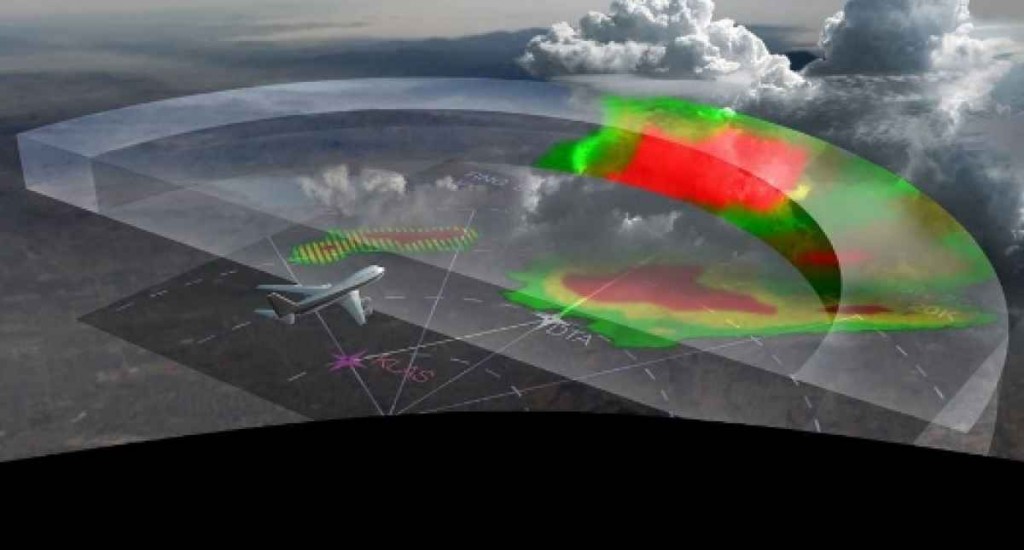

The airlines are occasionally delayed because of thunderstorms, fog, or snow. No mode of transportation is immune to the weather. In general aviation, we see it through the windshield and take precautions before trouble arises.

Sometimes you may hear about an aircraft that crashed in bad weather. The media are sometimes less than accurate in the portrayal of an aviation accident in their haste to provide an instant story. Aviation is a technical business, and a quick analysis will not take in all the facts that would explain why a particular accident occurred. In most cases, a “weather” accident should be more properly called a “judgment” accident because the pilot was not qualified to fly in bad weather or exceeded the limits of the aircraft.

Pilots first learn to fly under visual flight rules (VFR). from any clouds. Most pilots will choose much better weather conditions to give themselves more margin. Student pilots are given basic instrument instruction that is intended for emergency. Deliberate instrument flying requires additional training and forms the basis for the next typical step, the instrument rating, which then qualifies a pilot to fly in the clouds.

Just as boaters have to keep an eye out for weather, pilots must look for adverse conditions, but unlike many boats, an aircraft can outrun storms. Problems develop when the warning signs are ignored, and the pilot presses on.

What about midair collisions?

Instructor will invariably advise you that a midair collision will ruin the rest of your day we always look for other aircraft. In a typical year, there are about 4-8 collisions nationwide, and because they are so rare, they make the headlines. Most occur clear days within just a few miles of an airport.

To avoid close encounters with other airplanes, elaborate precautions taken to keep aircraft from tangling. At many busy airports, particularly with airline traffic, a control tower will provide takeoff and landing instructions by radio. New aircraft often have collision avoidance equipment installed to help detect nearby aircraft.

At airports without control towers, standard traffic patterns are established, so pilots will know where to look for traffic in the area. A common traffic advisory frequency is often used. Pilots advise their intentions on that radio frequency, and other pilots listen in to know what is going on.

Obviously, it’s important that aircraft be reliable mechanically. What’s the record on this?

Aircraft are a great example of over-design in engineering. Factory-built airplanes must meet rigid FAA design criteria. The structure of a typical training aircraft will withstand between 3.8 and 4.4 positive Gs. This means that if the airplane and contents weigh 2,000 pounds in normal level flight, the structure can safely handle up to 7,600 and 8,800 pounds in turns and pull-outs from dives, where the weight increases from centrifugal force. Routine flight is usually no more than two Gs.

There are very few accidents caused by an aircraft coming apart. Rarely, a pilot overstresses the aircraft in a pull-out or exceeds the top (redline) airspeed. In an automobile, if you over-rev the engine or take a corner too fast, you’ve exceeded the car’s envelope. Most drivers know the limitations of their cars and never have a problem. Pilots who adhere to the operating limitations never have to worry about the aircraft structure.

The other prevention area is in maintenance. Nearly all aircraft are required to have an extensive inspection each year, conducted by an FAA certified inspector. The engine, controls, and airframe are thoroughly reviewed and any problems are corrected.

Aircraft that fly for hire, such as the ones you would most likely be renting for training, have an additional every 100 flight hours. This could be as often as once per month.

As a result of this emphasis on continuing airworthiness, actual mechanical problems are identified in only about 7-10 percent of the accidents. Good maintenance is an investment.

What about running out of gas?

This should never happen. Prior to every flight, a prudent pilot will always ensure that there is plenty of fuel to get where you’re going plus a reserve.

We recommend a minimum of one hour of extra fuel upon landing. By following such guidance procedure, you can eliminate this concern entirely.

How does one stay up-to-date on the latest safety information?

Safety is one of the focus areas in aviation. Just as professionals in law, medicine, and business, pilots have a wide range of materials to help them stay current on safety procedures and regulations. AOPA members receive the association’s magazine, AOPA Pilot, every month to keep them abreast of the latest happenings.

The Air Safety Institute (ASI), a division of the AOPA Foundation, promotes general aviation safety through education, research, and training. ASI serves all pilots by providing free or low-cost education programs to pilots and flight instructors nationwide, analyzing safety data, and conducting safety research.

The Institute conducts more than 180 free safety seminars all over the country each year to teach pilots new techniques and to review research on safety studies and accident trends.

ASI also runs the leading flight instructor refresher program in the country. Instructors must renew their certificates every two years by regulation, and the institute offers a comprehensive program to help all instructors maintain proficiency.

ASI produces free online courses to make the education process interesting and enjoyable.

Additionally, many groups, such as flying clubs, flight schools and industry-sponsored organizations, offer lectures, seminars, and materials to help the education process.

Proficiency in any endeavor, recreational or professional, requires periodic review and refresher training. General aviation is no different, and pilots who practice regularly and seek competent instruction should enjoy an excellent safety record.

Bruce Landsberg is president of the AOPA Foundation.

http://m.aopa.org/letsgoflying/stories/080829safety.html

Comments are closed